By

Allan Graubard

Collages by Gregg Simpson

As a citizen of these realms, among others who have come and left their mark before me and others most certainly to do the same after me, I expect nothing less.

And, of course, there are some creatures – no doubt, from each species – who, for reasons of their own, not only replicate these kinds of mutations but do so with great success, so that they seem ever more natural, even to the point of one species infusing another with an external or internal form – sentinel reciprocations that heighten the stakes for each and every one of us attuned to it.

One further comment: Given the distinctions within this realm, equal to or more than those gained through descriptions of them, the act of writing takes on something of their animous. Words convulse, glitter, evaporate, reanimate, corporealize, convex, deracinate. Meaning follows and, while still compelling on its own, gains something more: sonic, even musical resonance that fabulates, one vowel or consonant at a time. And language, however quotidian it was beforehand, flashes with utopian salts – the better to eat clouds by; clouds that rise from the vernal Earth.

When

Gregg Simpson asked me to collaborate on a new work -- his collages, my

texts -- he mentioned he would send his collages to me. I

thought about it for a moment and replied this way: "Don't send the

collages. Just send the titles; that's enough." So he did, so

I wrote

these texts to his titles, and here, with his collages, is SIGHT

UNSEEN.

New Terrain is Old Terrain

The Delta region whose

waters pour into the Gulf has borne many multiform creatures through

the

centuries. Human and animal, bird and insect, fish and crustacea have

each come

under its spell with striking adaptations to this mercurial

environment. Whether

to facilitate movement on the ground, flight in the air or depth under

water,

there is little in regard to anatomy that has not changed to suite. A

local

hunter who lives most of the year in a watershed swamp has grown

thin-veined

webs between his toes to enhance balance on the spongy ground. A black

catfish

has generated a bony, horned protuberance just above its eyes to

mesmerize prey

with. A Jackbird has diminished in girth to elude predators by diving

faster

and soaring swifter while an orb-weaving spider has sprayed across its

web a

perfume that mimics mating scents in its diminutive world, and there

are many

more examples.

What this means when

considered as a totality, the various differences between animate

creatures

completing the rapport that defines them individually, shimmers just

out of

reach – a mirage in whose circumlocutions fact and fancy mingle.

As a citizen of these realms, among others who have come and left their mark before me and others most certainly to do the same after me, I expect nothing less.

And, of course, there are some creatures – no doubt, from each species – who, for reasons of their own, not only replicate these kinds of mutations but do so with great success, so that they seem ever more natural, even to the point of one species infusing another with an external or internal form – sentinel reciprocations that heighten the stakes for each and every one of us attuned to it.

Is this why there are

poets who mistake their metaphors for truths and scientists for whom

wonder is

a bridge to commensurate discoveries? Is this why there are

sparrows,

in a rain

pool or pond, that suddenly exchange their tufted heads for stellar

combustions

in the constellation Albertus Magnus, which commands during winter

nights? Is

this why there are dung beetles who curtsey before the great termite

mounds

that rise from the dryer uplands then lunge out to gather the soft

fecal matter

expunged from the nest, molding it into globes to lay their eggs in?

Is this

why an Oregon salmon transplant, having finally returned to its birth

harbor,

begins to think like a schizophrenic from Kronstadt circa 1921, with

all the

odds stacked against it and death a clean finale?

I believe the answer

to each of these examples is yes although I have little time or

instrumentation

to prove the point.

No matter. The

perceptible world, so quantum mechanics tells us, is not as we embrace

it.

This incertitude has

its charms.

These charms their

resplendence.

One further comment: Given the distinctions within this realm, equal to or more than those gained through descriptions of them, the act of writing takes on something of their animous. Words convulse, glitter, evaporate, reanimate, corporealize, convex, deracinate. Meaning follows and, while still compelling on its own, gains something more: sonic, even musical resonance that fabulates, one vowel or consonant at a time. And language, however quotidian it was beforehand, flashes with utopian salts – the better to eat clouds by; clouds that rise from the vernal Earth.

Putrefaction Ritual

In the Merida

Mountains of Venezuela, which arc in the northwest quadrant of the

country just

south of Lago de Maracaibo, there is a curious custom that its

ancient

indigenous peoples followed. It involves several rituals performed over

a dead

body. Seemingly, it did not matter whether that body were human,

animal, bird

or fish. Archeological evidence on that score is fairly complete. What

we don’t

know is just what happened and the sequence of each ritual.

Nonetheless,

putrefaction is key.

As the dead creature

putrefies, so too do the four organic offerings that surround it, each

geometrically placed above, on each side and below; when vectored

forming a

diamond-like shape. Dog teeth, fingers, neck vertebrae, paws, sea

shells, seeds

woven into small circular mats and other brief constructions are used

in this

manner to complete the circuit. The shape of the diamond no doubt

qualifies the

putrefaction of the dead creature, both framing and isolating it from

the

surrounding area.

Musical values also enter into this custom. Archaeologists have found primitive pipes carved from animal bones near enough to the burial to counter more cautious appraisals of their purpose. Perhaps devotees played those pipes during the ritual and then left them as tribute, a final salute to the transformation of life and regeneration to death and putrefaction.

Musical values also enter into this custom. Archaeologists have found primitive pipes carved from animal bones near enough to the burial to counter more cautious appraisals of their purpose. Perhaps devotees played those pipes during the ritual and then left them as tribute, a final salute to the transformation of life and regeneration to death and putrefaction.

Not long ago I was

invited to a performance of one of those pipes, which time and erosion

had not

appreciably damaged. A classical flautist had determined its range –

two octaves

– and, with embouchure, its note scale. Played in a concert hall, which

amplified the modest tone of the pipe, something that would not be

possible in

nature, unless played in a valley that supported echoes, an ancient

lyrical

music, simple and rich, enchanted me.

Was this music a means

for the dead creature to pass into putrefaction or was it less

symbolic,

something done to end the ritual for those who practiced it? I suppose

I will

never know.

On my last trip to the

Merida Mountains to continue my research, not so much in ancient

customs and

rituals now as their survivals in culture today, my colleague – whom I

will not

name – gave me a pipe dating back three millennia. She told me that I

deserved

the memento and would, in time, learn to play it. She was right. I play

it when

pondering the putrefaction ritual, and why, given its recurrence in

this area,

it was so important over so long a period of time. The organic diamond

form

around the dead body resonating with faint, deliquescent vibrato....

Cave of the Mandarins

Adroit cartographers

over the centuries have learned to communicate by inserting discrete

visual

clues or codes into their maps. An expert in the discipline can pick

them out

and, from time to time, discussion about them has entered into

scholarly

discourse, even if the practice is more playful than serious. Scholars

must

laugh like the rest of us.

That they do so amidst arcane analyses for a small audience comes as just another flourish in an otherwise routine culture that the academy prizes.

Recently, linguists from the University of Modena, Italy, have applied new translation techniques to this exclusive tradition. Coupling algorithms refined to detect subtext and structure in comparative groups of visual signs with newly conceived oneiric interpretations, they have produced a quixotic yet compelling narrative that has unearthed some disturbing values.

Maps portray landscapes, natural and urban. They also portray something of the dreamlife that unconsciously goes on when awake, and which, however much cartographers guard against it, seeps into their work. This does not mean that their maps are incorrect. They aren’t, given the historical period in which they drew their maps and the information they had to draw them. It does mean, however, that cartographers knew or felt or intuited, as they drew, that the line, circle, squiggle or vector spoke to them in a language that the clues or codes they left on the map referred to.

Here, though, is what

our linguist group has found.

Figured bodies of land

or water, outlined and inset with geographic features – such as plains,

lakes,

rivers, highlands, mountains, valleys, islands and the like – provoke

erotic

images; a tendency quite natural to us and which, I must admit, is a

predilection of my own. When viewed straight on or obliquely, images

emerge.

And however blurred or haphazard they might appear at first, a kind of

latent

visual subtext, more pronounced here, less pronounced there, they

slowly

clarify and then, as if part of the pulsation that keeps us alive,

disappear. A

slow natural flickering subsumes the map. Suggestive couplings, routine

seductive poses, wide glistening ecstatic eyes, moist curving lips,

full

breasts, an erect penis, a tangled vagina, the bare shoulder that

slopes to the

top of the arm, a hand with long reaching fingers, the slope of the

ankle, a

turned wrist, a sweaty cheek and other anatomical signs, many of which,

beyond

their status as cultural clichés, suddenly compel; transforming

the map into a

palimpsest of desire, both compassionate and cruel. Apparently, the

visual

clues or codes that cartographers inset into their maps attest to this

unique

facility, this envisioning, by drawing our attention to different areas

whose

boundaries interact. And what was once a recognizable geographic shape,

complete in itself, alters.

The terrestrial

cartography of surficial bodies becomes a medium that allows viewers to

see, as

it rises and as it passes, what attracts them most in this infectious

momentum.

The study group has also noted an eccentric disposition that figures,

not

humans, but animals in rut as well as large insects whose mating

choreographies

are as complex as they are savage, with death and ingestion a

concomitant

outcome; the female its dominatrix. Whether or not the translation of

other

animate creatures into visible images will occur, how they accord with

their

roles in nature, what sex leads and what sex follows, which is prey to

instinctual hunger, whether or not mimicry, masking and nurturance

claim their

pedigree are questions, surely among others yet defined, for further

study.

Gaston, not having the

heart to follow along blindly, prizing above all his sense of self, the

luxury

he deserved by way of it, and gaining in excess what he needed to feed

his

desires, out lasted them all.

Simpson

works in

the tradition of abstract surrealism. His paintings combine automatism

with

elements of landscape and the figure. They are improvised from simple

charcoal outlines

and then combined with the direct application of paint onto raw canvas.

The

meaning of the forms he creates changes with each viewer.

That they do so amidst arcane analyses for a small audience comes as just another flourish in an otherwise routine culture that the academy prizes.

Recently, linguists from the University of Modena, Italy, have applied new translation techniques to this exclusive tradition. Coupling algorithms refined to detect subtext and structure in comparative groups of visual signs with newly conceived oneiric interpretations, they have produced a quixotic yet compelling narrative that has unearthed some disturbing values.

Maps portray landscapes, natural and urban. They also portray something of the dreamlife that unconsciously goes on when awake, and which, however much cartographers guard against it, seeps into their work. This does not mean that their maps are incorrect. They aren’t, given the historical period in which they drew their maps and the information they had to draw them. It does mean, however, that cartographers knew or felt or intuited, as they drew, that the line, circle, squiggle or vector spoke to them in a language that the clues or codes they left on the map referred to.

One result, however,

is fairly clear: The envisioning that researchers have developed leads

them and

us into realms, both imaginary and real, that refract individual

passions while

valorizing anew our capacities in mapping. At the same time, the

technique is a

risky one, especially when it prompts the viewer to enact what he or

she has

seen without the usual cautions in place, preferably in a palace built

for that

purpose or, if lacking, then on any stage suitable for what’s to come,

luxurious or plain, large or small.

Saved at

Last

Yesterday, the

Department court ordered that the body of one, Gaston Thibeaux, be

exhumed from

its grave, illegally dug at the bottom of the levee near the curve in

the

river, and reinterred in hallowed ground. Catholic by birth, and as

tradition

has it, an altar boy along with his brothers, Frederic and Darceney,

when

Gaston finally came of age and took his place in society his manias and

behavior had changed – for him the better, for us the worse; but then

that

really depends on who you are. Pimp, thief, pirate, card shark,

burglar,

bigamist, impresario, embezzler or murderer, these were the stages he

passed

through and ever returned to.

With poor parents who

eked out a living insufficient to feed and house their three sons in

clean

surroundings, despite their rundown neighborhoods, and schooling an

eccentric

affair at best, Gaston did what he could get away with whenever the

chance

arose and whenever he made that chance his own.

Quick to seize on new

possibilities, whether of female flesh or the green that spells

“dollars,”

Gaston prospered or seemed to. The latter distinction he earned by his

wiles,

yes, but also by his talent in masking; quite simply, expressing

virtues he did

not in fact possess or believe in. Appearance being the arbiter of

taste and success in business, Gaston’s business, however that

might

turn, rarely let him down.

Within or outside of

the law, his projects gained the kind of prosperity that he could

indulge in.

With lavish parties thrown for friends, sailings into the Gulf of

Mexico on his

yacht, which at 46 feet was just long enough and antique enough to

envy,

especially by those he had yet to invite, his social standing rose,

placing him

squarely in harm’s way. Make no mistake, money and prestige – which he

adored,

however they came – did offer shelter from the storms that blew through

the

city, social and natural.

From his girls he had

gathered a bank roll that opened uptown doors and poker stakes, and all

their

cigar and gin-mixed winnings. Add in what he stole from different safe

deposit

boxes, whose entrance codes he filched, and there you have it. Exactly

how he

got the codes was not something he ever revealed. As a gentleman,

though, who

appreciated irony, he always replaced what he took with counterfeits so

poorly

rendered that their falsity was clear. No one could say that he left

those

boxes empty of the bonds they formerly held; however unusable they

were.

And this went on for

quite a while until complaints from gilded families, patchworked though

they

were, hit pay dirt with the mayor, gearing up for another election. No

matter

that Gaston had played them all, mayor included, and did it so well

that they

enjoyed losing -- a rare conclusion to a

finely tuned game. But then Gaston was a pro in the art of the sham, a

cheat in

whose refinements his victims found their pleasure. Avarice was one

thing; the

fun of winning another, and yet another the despair found in losing,

which

Gaston also used to keep the entire affair from crashing too soon. He’d

have a

winning streak, lose some then win again – without fail.

When the police finally

arrested Gaston, he went to jail willingly. He knew he’d come out on

top

however his trial went. He’d blast his way out of the courtroom if it

came to

it – easy enough in those days – then vanish among the islands, large

and

small, that stretched out from the coast for a final getaway south.

Of course, the police

caught a minority on their run to Venezuela or Columbia, where

extradition

treaties did not exist. But the majority were rarely heard from again.

The

living they bought from their new country, if similar to what they

fled,

offered richer amusements. Led by endless supplies of sexual mates,

heterosexual, homosexual, young, old, fat skinny, willing or unwilling,

the

latter the better to violate, the former impassioned enough and free

enough

with their passion to violate them – premiere inducements – vied with

power

hungry avatars set to consume their holdings the moment they could. The

two

groups kept them sharp enough to savor an ebullience they sometimes

shared.

When in his late 80s

he keeled over and died one hot, humid July afternoon, the city

devolved to a

potent mix of sweat and bitters, Gaston had not a cent to his name.

A year earlier his

gambling debts, which were themselves quite enormous, and a stock

market crash,

flattened his accounts. When he lost his several mansions and the

acreage he

had accumulated in different high-stakes crap games, that was that.

Having

enough in surplus to pay what he owed, and save something of the

respect that

others gave him, he thereafter lived on the largess of friends, who

found to

their delight that they could give as well as take, not having suffered

too

much from this or that scheme that Gaston thrived on.

As a corpse, Gaston’s

escapades, once a magnet for conversation after the usual diatribes

about race

and patrimony, faded off quickly. Laid there in the city

morgue,

just another slab of meat, it was time to forget him. Nonetheless, in

deference

to his wit and joie du vivre, those same friends who had come to his

aid when

he needed it, decided to save him from the crematorium. They took his

body by

stealth, dug a shallow grave at the base of the levee, rolled him into

it, and

covered him with enough dirt to keep the vultures, dogs, and other

scavengers

at bay.

Then the late summer

floods came and swept away the dirt above him; his right foot jutting

up from

the mud with just a bit of flesh hanging from the metatarsals -- a

mangey

blossom from a former time when Gaston called the shots.

Are we any the worse

for playing along with Gaston as he wove his cunning webs, which we

weave as we

can – taking his amusements for our own – however wealthy or poor we

are, with

those we love or hate or, more simply, live with, fearing the solitude

of

living alone?

I think not.

Although Gaston did

not in the end field a foolproof magic, in terms of morality or

conduct, the

grandiloquence with which he did it drew admirers and antagonists both,

as much

to drink from it as to magnify their own or lack thereof; his

narcissism

elevating theirs, his vanity a perfect excuse to try their luck at.

What could be better

in this world of feints and shudders that makes us bleed, and in

bleeding bleed

to death?

You first.

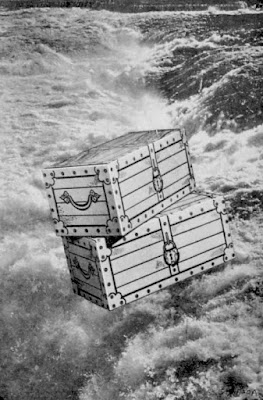

Niagara

Honeymoon

That night, unlike

other nights, I woke near dawn.

I knew this and that’s

all I knew: I had exhausted my luck. I lost. I was done.

Write me a letter when

you get there. That’s what you told me. I didn’t. Time had morphed into

wicker

Esperanto on Elba. Twilit June settling on the island; all that heat

and dust,

the tide, those sharp rocky beaches. As if I were nowhere, the idiot

neant

in a face struck by coffee, a face in stark hot despair.

Was this a dream, my

dream, despite my desire to forget it: Scene 3 -- the lip of the crag,

waters

ragging; whipped by the spray, toppling over…

I want to keep you

close, superfluous, paltry...

Tintype binoculars

wobble along the transept

There they are again:

yellow sheep shivering under fluorescent bulbs.

Through that doorway,

the slaughterhouse

.

Niagara honeymoon;

that’s what the brochure said. I held it up to you, above me, your face

the

face of the moon.

But it was our face,

not mine, that cinched to its nautical height the fictive flood, which

you

gave, breaking apart, your lips curling, teeth glinting, a nose like

some

shattered upland headstone.

Hope?

No hope.

No hope.

Don’t get me wrong. I

just don’t like charades. And in truth, I don’t like you.

I never did.

Ritual

Suddenly, as if the

light shifted into blue frondescence, I wandered back to that precious

moment

when I was born, emerging head-first from my mother’s cunt, slippery

wet, first

eyes opening, eternity my concubine years later when I found in a kiss

that

fateful lock, the transept where time returns to beginnings.

That was the start in whose

slow violin clichés…

There were tears

pinned to stars that flowed over us, night to night to night.

Take me in your arms,

airless fairground, subtitle in which “I” am little more than a mirror,

a

mirror of wool split at the seams.

Take me and forget me.

You will be better off if you forget me. You might even reclaim the

woman you

were before I squeezed your liver and raised your breasts to

Ecclesiastical

heavens.

But maybe, just maybe,

that’s what you want.

That, and an end note;

the beginning with no end.

This fur, this shadowy

furrow that flees from my feet…

Venus on

the Moon

They tell me, in the

song, that a woman cries out to the moon rising above a glimmering

lake. And as

the moon rises to its perihelion, the woman in the song opens her arms

to the

light that falls from the moon. But her sorrow remains. There is

nothing that

moonlight can do to calm the woman, and her cry extravasates.

They tell me that a

woman will sing this song when her husband or lover has died or left

her for

someone else. The longing and hurt in the cry that compels the song is

not

something that singing can absolve either.

She sings of cruel

truths and fickle passions, And the anger that scuttles her heart is

relentless

and useless.

They tell me that

after she sings this song, the grieving wife, the wounded lover,

understands

just how much she has lost; gaining this loss that undoes her.

They call this song

“Venus on the Moon,” and no one ever wants to sing it but they do. Things

happen

They

sing it.

Vindication

of

Species

I don’t want to say

anything, and this has nothing to do with poetry. I am sitting here in

the nude

on a hot humid summer night. The fan is whirring. The streets are

quiet. I am

tapping on these keys that make letters on a white screen. There is

nothing more

here. No hidden significance, no sur-text, no latent emotions, just

this

tapping. I will be doing this for the rest of my life. What more can I

say? The

words come. Simple quotidian words, neither rushed nor slow they come.

When this, our

species, is at its end, I can assure you that someone will be composing

words

and watching them turn into vapor…

.

Now my wife is getting

ready for bed. And when she lies down, nude, like me, she will be

another word.

Not one I have written but one she has written, for herself, for her

son, for

her sisters, her mother, brother, friends, and all those students that

she

teaches. She will be the word that they form in their mouths when they

speak of

her.

The same for me.

Is this vindication?

Perhaps it is. Then

again perhaps it isn’t.

The Door to

Infinity

The door to

infinity

opens to a corridor that runs below the street; a walkway for

pedestrians, some

of whom are asleep, some of whom are awake. Whatever state they are in,

when

passing each other they provide for each other. They emit whatever

distinction

they carry with them – a dream perhaps when sleeping, a memory perhaps

when

awake -- and absorb another’s. Their passing also charges a surplus to

the

interchange that keeps the corridor in tact -- for them and for other

pedestrians to come.

Now the corridor is

wide enough and high enough to allow pedestrians to pass each other

without

incident. At the same time, its construction – by whom or what agency I

cannot

say – places those within it at least close enough to enable the

interchange. A

brief shiver that traverses the shoulders, neck and head signals the

moment.

Point of view also plays into this, as does fantasy. Tales tell of two

pedestrians -- one coming, one going – who suddenly merge, separate and

continue on their way. Whether or not they do merge, and what happens

to each

having merged, is certainly a question to resolve.

That the structure has

existed for millennia, very much part of our history, is reason enough

to

celebrate. Not because “infinity” is a place a pedestrian can reach and

say,

definitively, this is where I am; this, my infinity, is also yours.

Rather, the

age of the corridor, its prestige in society, the various cultural

forms that

it gives birth to – in scholarship, the arts, literature, music, etc. –

the

reciprocal coming and going, the near tidal increase and decrease of

pedestrians in the corridor over time give to us a continuity we simply

can’t

do without; or haven’t up to this point done without -- which is

probably a

more truthful way of putting it.

That all this occurs

below ground is another inducement for wonder, especially because above

ground,

on the street, amidst the quotidian Hurley-burly, that other place,

unseen yet

poignantly felt, attracts, no matter how “down there” it is – as though

submerged

lateral movement had acquired a marvelously rich resonant charm in

itself, and

in which and by which we are able to live just a little more intensely.

Recently, an effort to

rationalize access to the corridor by mapping its aboveground entrances

has

largely failed. Once identified, a doorway thereafter vanishes as if it

weren’t

there at all and, in fact, had never been there. I suppose these

occurrences

speak to factors in the infinite that elude us, derived from yet

unexplained or

ever inexplicable encounters.

Nowhere to be found

after having been found, the door to the infinite finds us when we need

it or

when we least expect it. And when it appears, there is every reason to

open it

and begin a descent as others, having ended their walk, ascend,

re-entering a world

that they can now revive.

Dance of the

Infidels

In a smoky room on

Manhattan’s west side midtown, two pianists ponder the bridge to a trim

new

tune. It’s late afternoon and the sun angles in through a break in the

curtains. One is sitting on an old leather arm chair, eyes closed,

humming the

introduction. The other is at the piano tuned to notes that he plays in

silence, fingers poised above the keys. He does this when he’s unsure,

yet

listening to the urges rising within him; urges that he usually

transforms so

well into music.

This goes on for quite

a while until his colleague snaps his fingers, stands up, steps to the

piano,

leans down and plays two chords. They sound awkward enough when

isolated but in

tandem add up to something that the tune can use; as much to offset its

harmonic as to tip the rhythm forward.

The originator of the

tune then jots down the notation, looks at it for a moment, whistles

between

his teeth, lips barely open, and plays the thing out.

That night, after the

first set at the club, while in the dressing room, the pianist tells

his band

that he’ll do the first song solo. It’s a new thing he’s written and he

wants

to try it out.

“I’ll play it. Then

you all follow, drummer, bass, sax, trumpet. We’ll do the repertoire

but start

up in that order: drum solo, bass and drum duet, trio, quartet. Take as

long as

you want. Then I’ll join in.”

They have a few

drinks, smoke a cigarette, snort some coke, talk a bit with several

journalists

who’ve dropped by with their ladies and lay back for a few more

minutes. Then

its curtain call.

The pianist walks on

stage, sits down on the piano bench, hands in his lap and waits for the

crowd

to quiet. He waits a little longer, placing his hands on the keys. Then

he

begins. When he gets to the bridge he realizes again how perfect it is;

just

what the tune needed; keeps the opening and closing sections

off-balance enough

to entice deeper listening. And he plays on as he wrote it: for a

memory, one

of several memories, that kept returning a few afternoons just as he

was

waking. Whether they were real or not, formed by events he experienced

in sleep

or by day, when he was conscious enough to know he was awake, isn’t

something

he can say.

He doesn’t split hairs

on such things either. He accepts them for what they are and how they

present,

and enjoys or dislikes them, or some portion of both, then moves on.

Be that as it may, he

senses that this memory, those memories, orbit about a dreadful sun

that burns

up through a vortex composed of clouds, rain, dust and bits of

petrified

lightning whose thin blue magnetic borders crackle lowly.

Amidst the centripetal

force of the vortex, which he no doubt creates, if only to stabilize

the tale

that this memory, these memories, tell, he sees this: He and his wife

are

walking along a trail beside a deep gorge. A body of water -- river,

lake, or

pond; it’s too small to be a lake from

so high up yet it could be – glitters far down at the

bottom of the gorge. Transfixed by the

glittering light reflected off the water, they forget where they are.

The trail

climbs and falls, turns and rises again toward a summit as far above as

the

water in the gorge below.

Sudden cool breezes

appear and vanish. Time escapes them. Their thoughts dwindle to the

regular

sway of their walk, the faint signature of their clothes rubbing

together, the

shallow pulse of their breathing. It is as if they have been here for

as long

as they have been alive. It is as if the trail, centuries old, were a

medicant

medium and they its servants. It is as if the scene they give birth to,

this

scene from that memory, these memories, conveys them to a second life,

a

separate parallel vivacity that in sharing, he absorbs, and as he does,

she does,

along with the scene from that memory, these memories.

It all happens ever so

slowly.

He knows then that

he’s been playing, that he is playing the new tune he wrote with that

bridge

his colleague came up with, and that the entire thing is just about to

end.

He ends it, sits up,

folds his hands into his lap and closes his eyes.

The audience, first

silent, not knowing how to respond, stunned a bit by the journey the

tune has

taken them on, breaks into scattered applause.

He swivels around.

“Dance of the

Infidels,” he says, “a new tune.”

Then the drummer walks

on with his sticks and brushes, sits at his kit, pauses and starts in…

Gregg

Simpson

and Allan Graubard

Bowen

Island, BC; / New York, NY

.About

the Writer and the Artist

Allan

Graubard’s poems, fiction, theater works, and literary and theater

criticism are published or performed in the U.S., Canada, Brazil,

Chile, U.K., and the E.U., with translation into numerous languages. He

has appeared as reader, guest artist, and lecturer in the U.S.

(New York, Washington D.C., New Orleans and Lafayette, Louisiana,

Wesleyan, Connecticut, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boulder,

Colorado); Canada, (Toronto, and Montreal); U.K. (London and Oxford);

Croatia (Dubrovnik and Hvar); and Bosnia Herzegovina (Sarajevo).

His books include: Into the Mylar Chamber: Ira Cohen, Western Terrace, A Crescent by Any Other Name, Targets, And Tell Tulip the Summer, Roma Amor, Fragments from Nomad Days, Ascent of Sublime Love, and more. He is co-editor with Thom Burns of Invisible Heads: Surrealists in North America – An Untold Story.

Theater works include: For Alejandra, Woman Bomb/Sade, and with Lawrence D. “Butch” Morris: Modette and Erotic Eulogy.

His books include: Into the Mylar Chamber: Ira Cohen, Western Terrace, A Crescent by Any Other Name, Targets, And Tell Tulip the Summer, Roma Amor, Fragments from Nomad Days, Ascent of Sublime Love, and more. He is co-editor with Thom Burns of Invisible Heads: Surrealists in North America – An Untold Story.

Theater works include: For Alejandra, Woman Bomb/Sade, and with Lawrence D. “Butch” Morris: Modette and Erotic Eulogy.

Born

in Ottawa

in 1947, Gregg Simpson grew up in the rainforest environment of the

west coast.

His work has been exhibited in museums and galleries in Canada, the

U.S.,

Europe and South America and is included in over 100 private and public collections internationally. His work has been included in the major exhibitions and books on

ontemporary Surrealism.

Europe and South America and is included in over 100 private and public collections internationally. His work has been included in the major exhibitions and books on

ontemporary Surrealism.

In 2012 and 2013

a retrospective of his work from 1970-’75 toured museums in Spain and

Portugal.

In May, 2000 he had a solo exhibition in a castle in Italy which became

the

subject of a BRAVO TV television documentary, A

New Arcadia, The Art of Gregg

Simpson:

www.greggsimpson.com/Videos.html

No comments:

Post a Comment